The Takeaway: The 4% Rule tells you two things.

- First, it lets you know how much you can annually tap from your retirement nest-egg without it running dry.

- Second, it tells you how big your nest-egg needs to be to cover your retirement income needs.

What’s not to love? 😀 This post is a step-by-step guide to drawing down your nest-egg–and figuring out how big it needs to be to meet your income needs.

$$$

Aloha autumn Boomer! Let’s cut to the chase. Here’s what can happen when you don’t know how to manage a sizable nest-egg.

It seemed like a lot of money at the time.

My friend’s Aunt Susie was widowed at 51. Fortunately, her husband left her enough money to live comfortably for another 30 years. That seemed reasonable, given that she was in a fierce battle with stage 4 cancer at the time.

Boomer, 30 years have come and gone. Doctors periodically beat back Aunt Susie’s cancer. She shows little sign of exiting any time soon.

But now she’s out of money. She’s contemplating taking in a boarder.

She needs and wants money.

Had the 4% Rule been developed earlier, Aunt Susie might have a different life today.

What’s the 4% Rule?

The 4% Rule is a method of drawing down your nest-egg so it lasts as long as you do.

Specifically, it tells you:

- how much you can withdraw from your nest-egg without it running dry and

- how big your nest-egg must be to support that withdrawal and meet your income needs.

The 4% Rule is designed to make sure your money lasts as long as you do.”

How do I know the 4% Rule works?

Bill Bengen’s landmark study revolutionized how retirees tap their nest-eggs so they don’t run out of money.

Enter Bill Bengen. MIT grad, certified financial planner, and superhero to finance nerds worldwide, Bengen didn’t want his clients running out of money. As such, he got to work and began analyzing economic and financial data as far back as 1926.

In 1994, his landmark study was published in the Journal of Financial Planning. The study

Based on a landmark study, the 4% Rule is the short-hand name for drawing down your portfolio.

was dubbed the 4% Rule, but it could just as easily been called the 3%, 4%, or 5% Rule, as you’ll see shortly. It has become the gold standard of portfolio withdrawal.

(A description of how Bengen developed the 4% Rule is found in footnote 1, along with links to his original work, other researchers that have replicated his work, and links to financial services firms that use the 4% Rule with their clients.)

The 4% Rule is the gold standard of nest-egg withdrawal.“

How does the 4% Rule help ensure my nest-egg lasts as long as I do?

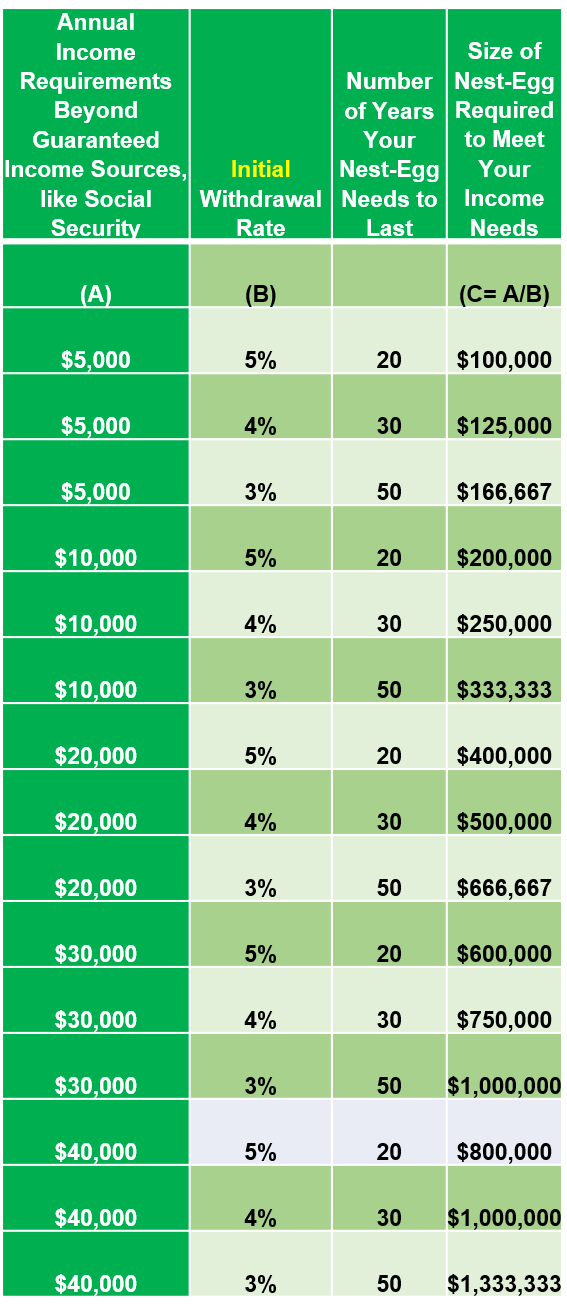

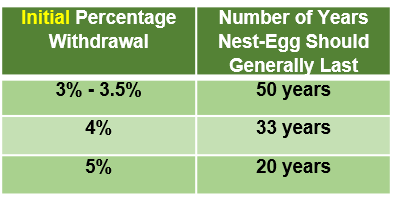

Bengen’s research showed how long your nest-egg lasts depends on your initial withdrawal rate, as shown in the chart at left.

Bengen, William P. “Determining withdrawal rates using historical data.” Journal of Financial Planning, vol. 7(1), pgs. 171-180, 1994.

As you can see, the lower your initial withdrawal, the longer your money lasts.

Bottom line. Even if your nest-egg gets perilously close to running out, it shouldn’t run dry if you stick close to the initial withdrawal percentages stated at left. You also have to allocate the money in your portfolio in a certain way, which we’ll discuss later.

For now, it’s vital to know how to draw down your nest-egg using the 4% Rule.

Step-by-step: how exactly do I draw down my nest-egg?

Make it snappy! Walk me through the 4% Rule.

Step 1: Decide what your income needs are and how long you need your nest-egg to last.

Step 2: Based on the answers to Step 1, decide what percentage you want to initially withdraw from your nest-egg. Refer to the chart above for guidance. Say it’s 4%.

That 4% is a your retirement starting salary.

Step 3: Each year thereafter, give yourself a raise.

Your raise is the previous year’s rate of inflation, easily found by scrolling down this table. For example, If inflation in the preceding year was 1%, you’d give yourself a 1% raise.

Just like if your boss came to you and said, “We’re giving you a 1% raise.” You’d take your current salary, add 1% to it, and that’s your new salary.

This new salary is how much you withdraw from your nest-egg.

Sometimes the 4% Rule is reported incorrectly.

Sometimes the 4% Rule is reported incorrectly.

The 4% Rule is not withdrawing 4% from your nest-egg each year. The 4% comes into play only for your initial withdrawal. From year-2 onward, your retirement salary is adjusted–typically increased–by the rate of inflation.

The 4% Rule is not withdrawing 4% from your nest-egg each year.”

Give me the step-by-step real-world example.

Say you’ve squirreled away $100,000 to supplement your guaranteed income, like Social Security, pension, annuities, etc. You want this $100,000 to last 30 years. The green chart shown earlier indicates a 4% initial withdrawal should last about 30 years. As such, you use an initial withdrawal of 4%.

Here’s a table (below) of how this would look. I’m using data from 2005 – 2007 so that you can see where I pulled the inflation numbers. Please, Boomer! Click the link and make sure you can match the inflation data I’ve used. This step is key to not outliving your nest-egg.

Table 1. Arithmetic showing how to draw down your nest egg.

Note: You can ensure you give yourself an accurate raise by matching the inflation numbers in the table above with the inflation data here. Give it a try!

Table Source: Graphic depiction inspired by article entitled “How can I make my retirement savings last?” Fidelity Viewpoints, August 27, 2018.

What did the table tell me?

Here’s what the table says.

Say you’ve got $100,000 saved and want it to supplement your other guaranteed sources of income, which might include your Social Security, pension,annuities, etc. You want to draw this $100,000 over the next 30 years. As such, you choose a 4% initial withdrawal and calculate your Year-1 retirement salary.

Year-1 salary. Here’s your starting salary.

$100,000 nest-egg x 4% initial withdrawal = $4,000 retirement starting salary

Thus, your annual starting retirement salary is $4,000.

At the end of your first retirement year, you see that inflation ran 3.4%–like it did in 2006.

As such, you give yourself a 3.4% raise in year-2.

Year-2 salary. Here’s your year-2 salary:

$4,000 previous year’s salary x (1.034 previous year’s inflation factor) = $4,136.

Let me walk you through the arithmetic.

Since these are your life-long earnings, lets do this one more time for year 3.

Year-3 salary. At the end of year-2, you see inflation was running 3.2%–like it did in 2007. Give yourself a 3.2% raise, Boomer!

$4,136 previous year’s salary x (1.032 previous year’s inflation factor) = $4,268.

Capeesh?

You do this every year until the director yells “Cut!” and you exit stage left.

Think of your initial 4% withdrawal as your retirement starting salary. Every year thereafter, you get a raise based on the rate of inflation. Your initial salary, plus your raise, is how much you withdraw from your nest-egg.”

Feeling nervous?

I know it doesn’t show, but you’re making me nervous.

Boomer, if you feel nervous taking a raise when your nest-egg goes down, then forgo your raise. Wait until the market stabilizes. If you feel like you should take a bit of a salary cut, then do it!

On the other hand…

If you’re tempted to take a raise that exceeds inflation because markets are soaring, I have two words: stifle yourself. You need that cushion for when financial markets crater–like they did in 2008.

How does the 4% Rule let me figure out how big my nest-egg must be?

Tell me! Do I have enough money to retire? Am I going to run out of money? (Don’t be this woman!)

Once you know how much income you’ll need in retirement, the 4% Rule can help you figure out how big your nest-egg must be.

You don’t have to ask, ‘Do I have enough money to retire?’ Nor do you have to ask ‘Am I going to run out of money?’ Boomer, since you know the 4% Rule, you know the answer.“

Boomer, feel free to seek confirmation and guidance. But be armed with knowledge before you do. After all, no one cares as much about your money as you do.

(If you’re already retired, this table below will also tell you if you should go back to work.)

The table below shows how to figure out how big your nest-egg should be. We’ll talk about it on the other side.

Table 2. Above and beyond your guaranteed income, how big your nest-egg needs to be so all your retirement needs are met.

Source: Boomer Money and More calculations based on Bengen, William P. “Determining withdrawal rates using historical data.” Journal of Financial Planning, vol. 7(1), pgs. 171-180, 1994.

What did the table say?

Above and beyond your guaranteed income, like your Social Security, pension, annuities, etc., this table shows how big your nest-egg needs to be to support the income you require. Say you need $10,000 a year above your guaranteed income. You need it to last for 30 years.

Here’s the arithmetic.

Sometimes I like to sit out here and recite the 4% rule.

How much annual income you require ÷ your initial withdrawal

= required nest-egg size.

$10,000 year ÷ 4% withdrawal = $250,000 nest-egg.

An income of $10,000 a year requires a $250,000 nest-egg.

Break time.

Let’s face it, Boomer. This whole post is a total buzz kill. 😥

I know it.

What?!! Your’re still not tracking expenses?

You know it.

It’s also why you’re tracking your expenses. When you know where the money goes, you know how much you need to live on. You know where to cut the fat.

What?

Still not tracking those expenses? (You’re.Hurting.My.Feelings.)

Check out this post. It’ll go a long way in helping you figure out where your money goes.

If you think you’ll need a bigger nest-egg than you’re on track to have, follow the steps of other Boomers to build income. It’s all in footnote 2.

Now let’s bring it home with this last bit of information.

Four requirements for the 4% Rule to work (the first of which I don’t love–but good news follows)

To work, the 4% Rule requires that between 50% and 75% of your portfolio be in stocks–too many for some folks.

Boomer, in the Asset Allocation Series, we showed why it’s not just enough to have money in the bank. It’s how that money is distributed between stocks and bonds that counts.

It’s no different with the 4% Rule. It also requires your money to be allocated in a specific fashion.

Here are the four requirements necessary for the 4% Rule to work. (I don’t love the first one.)

First, you need to maintain a portfolio containing between 50% and 75% stocks (specifically S&P 500 – index fund – stocks).

Second, the remaining 25% to 50% of your portfolio needs to be in 10-year Treasury Bonds (available at such brokerage houses as Fidelity and Schwab).

Third, your portfolio needs to be rebalanced once a year to maintain the above distribution of stocks and bonds–as discussed further here and here.

Fourth, you need access to a secure location where you can scream in anguish at the thought of these requirements.

As always, when I say stocks, I’m talking stock S&P 500 stock index funds.“

And here’s why.

Houston we have a problem.

Houston, we have a problem.

The problem is this: a 75% stock asset allocation, for retirees over age 60, flies in the face of traditional asset allocation rules of thumb. Even Bengen acknowledged this problem (p.176),

Here’s the thing.

You need those faster growing stocks for your portfolio to increase in value as you’re simultaneously drawing your portfolio down. The growth offsets your withdrawals.

Boomer, I know. So much stock in a portfolio gives some of you real heartburn.

Fortunately, I bring good news.

Finance faculty at Trinity University expanded Bengen’s 4% Rule for use with more conservative porfolios. These portfolios modify these 4% Rule requirements and then show you what the consequences of these modifications are.

Frankly, I think they’ll let you sleep better at night. And there are some other variations on the 4% Rule I’ll share in upcoming posts that’ll make this even more palatable.

But first things first.

To build a house, you’ve got to lay the foundation. The 4% Rule was the foundation; the gold standard of foundations.

All the more comfortable alternatives build on the 4% Rule, which you now understand.”

Hi there! I’ve got some good news and more comfortable alternatives. (Stay tuned!)

You now know more about the 4% Rule than all your friends and most civilians.

You have information that Aunt Susie never got the chance to learn.

Most importantly, you know if you have enough money to last a lifetime.

(Not sure?) Pour yourself an adult beverage and give the post another read. It’s really just grade school arithmetic. It’s just that it’s new and applied in a different way.

Don’t outlive your money, Boomer.

You got this.

$$$

P.S. Boomer, if you found value in this post, and if you don’t mind, could you forward this post to a friend, or scroll to the bottom of the page and post it on social media? U Rock!

Footnotes

1Information about the 4% Rule. You can read all about William Bengen’s 1994 landmark study, “Determining Withdrawal Rates Using Historical Data” here. Essentially, Bengen ran a sample investment portfolio through the worst 50 years in U.S. financial history. These miserable periods included:

- the Great Depression (1929 – 1931),

- the mini-resurgence of the Great Depression (1937 – 1941), and the

- wretched recession of the early 1970s (1973 -1974)—which had falling stock prices and spiking inflation, both serving to further lower investment returns.

The total data range he studied was from 1926 – 1992. His work did not include the Great Recession of 2008, which was of shorter duration than the Great Depression and occurred 14 years after his study was published.

Using an investment portfolio composed of 50% S&P 500 stocks and 50% Treasury bonds, he evaluated how well the portfolio would have fared for the years 1926-1976. Using successive 50 year periods, he analyzed how well the portfolio did from 1927 – 1977, then 1928 – 1978, then 1929-1979, etc. And so it went until the final 50-year period from 1972-1992.

He rebalanced each year.

He explains his methodology here. (See appendix). (And for you nerds after my own heart, selected expansions of his work are here and here and here.)

Other researchers have replicated Bengen’s work with the 4% Rule–the most famous of which are described here.

Financial services firms, like Fidelity, Schwab, and Vanguard,commonly reference the 4% rule in client publications designed to make your money last.

2You have no nest-egg or your nest-egg is too small.

Boomer, if you don’t have a nest-egg, or it’s too small, you’re not alone. There are common and uncommon steps you can take to build a retirement nest-egg.

First, the common ones.

- If you’re working, continue to do so and start saving like mad;

- If you’re no longer working, consider going back to work full- or part-time.

- Delay Social Security until you’re 70, since your monthly benefit increases 8% a year (uncompounded) after your full retirement age, up to age 70.

- If you’re already taking Social Security, and you can afford it, suspend your benefit until you turn 70 so it can continue to grow.

- If you’re working and worried about earning too much to qualify for Social Security, forget it. True, they reduce your Social Security while you’re working, until you reach your full retirement age. But once you hit your full retirement age, they start giving it back to you. It’s a deferral not a loss of Social Security when you do this.

Now for some uncommon steps.

Pull out your copy of Seven Steps to Not Outlive Your Money, available to subscribers. (Unsubscribe at any time.) Focus on those particular steps that describe:

- what Boomers are doing to create additional income;

- how Boomers are stretching the income they now have—like where they’re choosing to live; and

- habits and behaviors Boomers are avoiding so they don’t spend money that belongs in their nest-egg.

Think outside the box. Track your expenses so you can capture that money that slips through all of our fingers. (You’re a business, Boomer. And a business has to know what’s coming in and what’s going out if it’s to remain viable.)

You got this.

$$$